My landscape architecture masters thesis is available online through the University of Washington. Here I share the cliff-notes versions, with lots of illustrations.

Landscape architects may not be able to affect who owns

urban land and what is built on it, but we can equip ourselves to best support

projects that work toward social and economic equity in cities. This research

thesis aims to advance the knowledge of landscape architects who want to add

value and efficiencies specifically targeted for the design of equitable community-owned

housing. Using commons theory, case study research, and other literature, this

thesis proposes a framework in which housing and urban design can afford better

settings for community ownership to take place. The proposed toolkit contains

three overarching recommendations: to make places physically and emotionally

connected; supportive of community life; and changeable over time.

|

My experiences have led me to ask what makes an equitable

community and as a landscape architect and urban designer, how to design

these spaces. My research question is: What types of spaces support

inclusive, community-owned placemaking?

The idea of community control is widely supported in theory but largely unimplemented in practice, as demonstrated by current and widespread urban economic displacement. Community ownership is a community control, affordable housing, and anti-displacement strategy that matches legal ownership and governance to the psychological ownership people feel over their communities.

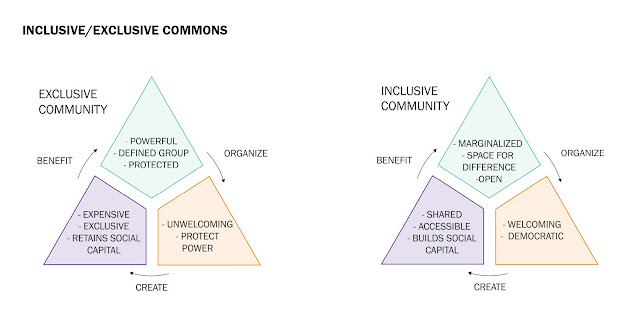

Commons theory reveals how community ownership works. The process of creating commons begins with people who organize themselves to create resources that in turn benefit the community members who made them. This process has produced non-commodified housing, such as limited-equity cooperatives, nonprofit housing associations, squats, and community-owned development, that can support pathways to affordable housing, resiliency, and racial equity.

Original case study research grounds these theoretical ideas. The first three case studies utilize research I conducted in Denmark on three distinct models of community-owned housing. Back home in Seattle I studied Othello Square. Analyzing the cases, especially as to their manifestation of commons theory and commoning practices, forms a primary basis for my design recommendations.

Case study profiles

Norrebrogade 105-107 is one of many private housing

cooperatives in an urban Copenhagen neighborhood. These buildings were

converted to co-ops and the interior courtyard was cleared of old industrial

buildings. Now the residents collectively manage the courtyard and have work

parties to help maintain it.

Tinggaarden is a nonprofit housing association estate in a

Copenhagen suburb that is organized into groups of eight to twelve households

that share a courtyard and common house where there are mailboxes and laundry.

Most units have their own small yard.

Christiania was originally a squatted military area in the

heart of Copenhagen and everything there has been made or maintained by the

residents for the last 50 years. It is a mixed-use district open to the public

and ultimately controlled by its residents.

Othello Square is a community-owned development in Southeast

Seattle meant to specifically address the community’s needs and developed over

years of local planning. The first buildings are under construction as of May

2020. Othello Square planned to include the first purpose-built limited-equity

housing cooperative in Washington State. One of the partners is the

Multicultural Community Coalition, developing a new model of a co-owned shared

office and meeting space for small community-based organizations that are

themselves at risk of displacement. The plaza in the center is being designed

by Weber Thompson landscape architects. It will be a pedestrian environment

connecting all the parts of the campus and the neighborhood.

Commoning practices are activities and institutions

that people participate in together that either create or maintain resources –

tangible like places and intangible like social capital.

Lowered thresholds to belonging are important because

commons do not necessarily provide benefits to those who do not belong to them.

In order to benefit society at large, it is critical that commons are open,

accessible, and welcoming, with lowered thresholds to entry specifically

targeting groups that are usually systemically excluded.

Agency to place-make satisfies the human need to shape one’s

environment to make a home. Placemaking is part of the bundle of rights

encompassed by ownership and called for at an urban scale by the ‘right to the

city’ movement. Self-governed communities have the ability to distribute rights

of placemaking along nested scales of private-ness so people have agency they

need to personalize their home, but also collectively best meet the needs of

the community.

The commoning practices that form the basis of my design recommendations can be seen as performance characteristics in the tradition of Kevin Lynch in Good City Form (1981). The effectiveness of the design toolkit can be judged by the extent they afford commoning practices. Similarly, in his 2017 chapter “Urban Commoning in Cities Divided,” Jeffrey Hou suggests a move from “a focus on shared resources to the production of social relationships” in designers of the commons.

These commoning practices are themes that emerged from my

case study research and are realized differently in every community:

1.

Networks and partnerships. Networks are

relationships between people and organizations that might be loose or fleeting

while partnerships are more established connections sharing resources, labor,

and knowledge.

2. Welcoming all people. A welcoming policy is important for community ownership to not be an exclusive enclave. Community ownership builds resources, which must be shared as to not perpetuate concentration of wealth and resources among the privileged.

3.

Informal everyday life. By interacting on

a personal level stereotypes can be broken down and the foundation for

understanding can emerge.

4.

Traditions and rituals. Gatherings of all

types provide opportunities to build relationships, create, and share culture

both for the facilitators and all who participate.

5.

Transformation in place. Community-owned

housing is an anti-displacement and place-keeping strategy by which people can

stay in their communities under different governance structures.

6.

Shared stewardship. When implemented

thoughtfully, shared stewardship can lead to close social cohesion, pride in

place, and a resource-rich housing commons.

7.

Individual personalization. Individual

personalization adds to a commons in two main ways, allowing people to feel at

home, and adding to the overall uniqueness of a place over time.

Another layer of information becomes apparent when considering how commoning practices apply to phases throughout the lifecycle of a project. In general, lowering thresholds to belonging happens in the early stages and placemaking happens later on, but both are important throughout.

PHYSICALLY AND EMOTIONALLY CONNECTED

CONNECTED AND NEARBY. Being physically situated in an accessible area and being part of daily routines. For example: The Othello Square master plan shows how the layout of the site is connected to the light rail station how pedestrian spaces are connected through all the parts of the site.

LOVABLE is about people

feeling connected by the project being suited the local community’s needs

and visibly reflecting the material culture of communities involved. For

example, at Othello Square a lot of community members are immigrants and refugees.

Weber Thompson’s planting palette uses plants from all over the world so people

see something they can relate to.

SPACE TO BE is about creating inclusive public space that has places to hang out and might be

activated by businesses. For example, in front of the general store in

Christiania is a classic bumping place where locals go to chat. In December a

tent lit up with Christmas lights marked the place’s importance.

PLACES TO GATHER is about intentional gatherings including public events that can bring people in. For example, the Othello Square Multicultural Community Center floorplan has a variety of spaces that can be used concurrently in different ways and spill over into the courtyard.

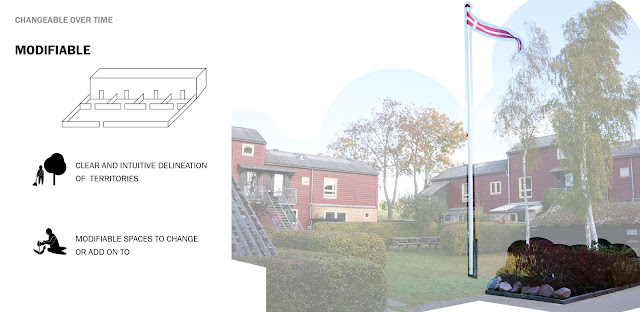

CHANGEABLE OVER TIME

ADAPTIVE is about staying in place. What are the physical changes that need to be made? For example, the Norrebro courtyard was converted and the path reflects the historic access road.

MODIFIABLE is about places that can be changed together by the residents over time. For example, in Group

B at Tinggården the common green has been modified with a flagpole in memory of

a neighbor and rhododendrons that were planted to remove a parking space.

FLEXIBLE is about changes on a shorter timeframe such as events and places designated

for individuals or families to make

their own. For example, The New Holly Market Garden across the street from

Othello Square has a farmers market that Othello Square will connect to.

Overall, this has the potential to support community ownership

that provides affordable housing, long-term stability, opportunity to

build social capital, and community control. And with multi-scalar

organization, the potential to contribute to resilient, dense, and more

equitable cities.

I offer this work because community ownership has been shown to be a viable model of organizing society that promotes economic and social equity. By focusing on enabling community-specific commoning practices that work toward agency to place-make and access to belonging, design has the potential to contribute to the success of community ownership.

Comments

Post a Comment